Ann Hart Stewart was one of the first contributors to this blog. Her grandparents, Charles and Hattie Ruhsenberger, resided at 5930 East Washington Street. Other relatives lived nearby on Burgess Avenue. Ann's photos and stories have chronicled life near the corner of East Washington Street and Arlington Avenue. She contributed a fun story about a famous cat, who lived across street. You may read more about her family by clicking the "Ruhsenberger" or "Stokesberry" links below. Recently, she found another historic photo of her family members snapped in 1937.

The Ruhsenbergers occasionally took breakfast picnics. Mr. and Mrs. Ruhsenberger had three children, Roger, Henrietta, and Patricia. Sometimes, the families would get up early and drive to Christian Park to enjoy the beauty of nature and each other's company. They had to reserve a grill ahead of time for cooking. Not everyone loved the experience. A very young Ann Hart noted that she was not so keen to be up so early and away from the warmth of her kitchen at 5930 East Washington Street. The Ruhsenbergers are all now gone from Irvington and even their family home was demolished in 1957. Thankfully, folks like Ann Hart Stewart help us to remember.

Tuesday, November 20, 2018

Sunday, November 11, 2018

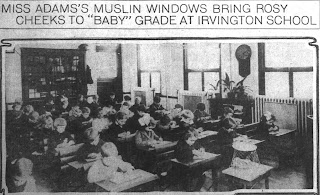

Miss Estella Adams Wrote a Children's Book

In 1916, Indiana celebrated one hundred years of statehood. Local residents put on pageants, plays, and festivals. Several histories also appeared that year including one by a local Irvington teacher, Estella Adams. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, a local printer, published her work, Pioneer Life for Little Children, and sold the book throughout the United States. Miss Adams taught first grade at School #57 at the time so the smaller children were her primary audience.

She likely wrote the book while living in her beautiful new home at 440 North Irvington Avenue. She resided there with her mother, Margaret, and her brother, George. City records indicate that Miss Adams took out a building permit in 1911 for the property. It is unknown how she was able to afford such a grand home, but the Indianapolis News in 1905 published that she had invested $200 in the Citizens Gas Company so perhaps she had earned a comfortable living with some shrewd investments.

Pioneer Life was illustrated by Harrison Fisher and Marie Stewart. In the first third of the book, Miss Adams wrote about the lives of the Indians who lived in the Midwest. The illustrations in this part of the book are realistic and somewhat romanticized. Her treatment of the native peoples is much more respectful than many narratives of her day. The illustrator of this section chose to draw images of the Plains Indians and not those who actually dwelled in Indiana. In the second third of the work, Miss Adams described life for the white people who moved into the area. Like most children's histories, this section is sanitized. The Indians, according to the author, moved away because the deer and the bison were no longer as plentiful. How does one tell first graders that their ancestors actually forced the native peoples from their land and on to reservations? The illustrations in this section are more like etchings. She does challenge the children to think about the lives of the two groups.

Indian girls carry wood for the fire.

They string red and yellow beads.

They make pretty baskets.

The baskets are made of sweet grasses.

The girls make bowls of clay.

They paint the bowls after they are dry.

They carry water in these bowls.

Can you make a clay bowl?

Miss Adams dedicated the book to the children of Irvington. She and her family continued to dwell in their Irvington Avenue home until 1919. For unknown reasons, she took a leave of absence from the Indianapolis Public Schools and eventually moved to California. The Rush family purchased her house.

Sources: "Recent Publications," Indianapolis Star, August 6, 1916, 6; "Written Book on Pioneer Life," Indianapolis News, December 7, 1916, 13; Obituary for Margaret Adams, Indianapolis Star, July 8, 1933, 10.

She likely wrote the book while living in her beautiful new home at 440 North Irvington Avenue. She resided there with her mother, Margaret, and her brother, George. City records indicate that Miss Adams took out a building permit in 1911 for the property. It is unknown how she was able to afford such a grand home, but the Indianapolis News in 1905 published that she had invested $200 in the Citizens Gas Company so perhaps she had earned a comfortable living with some shrewd investments.

Pioneer Life was illustrated by Harrison Fisher and Marie Stewart. In the first third of the book, Miss Adams wrote about the lives of the Indians who lived in the Midwest. The illustrations in this part of the book are realistic and somewhat romanticized. Her treatment of the native peoples is much more respectful than many narratives of her day. The illustrator of this section chose to draw images of the Plains Indians and not those who actually dwelled in Indiana. In the second third of the work, Miss Adams described life for the white people who moved into the area. Like most children's histories, this section is sanitized. The Indians, according to the author, moved away because the deer and the bison were no longer as plentiful. How does one tell first graders that their ancestors actually forced the native peoples from their land and on to reservations? The illustrations in this section are more like etchings. She does challenge the children to think about the lives of the two groups.

Indian girls carry wood for the fire.

They string red and yellow beads.

They make pretty baskets.

The baskets are made of sweet grasses.

The girls make bowls of clay.

They paint the bowls after they are dry.

They carry water in these bowls.

Can you make a clay bowl?

|

| Pioneer Life for Little Children appeared in print on August 6, 1916, and was used throughout the state of Indiana. |

|

| Estella Adams, who taught at School #57, dedicated the book to the neighborhood children. |

Miss Adams dedicated the book to the children of Irvington. She and her family continued to dwell in their Irvington Avenue home until 1919. For unknown reasons, she took a leave of absence from the Indianapolis Public Schools and eventually moved to California. The Rush family purchased her house.

Sources: "Recent Publications," Indianapolis Star, August 6, 1916, 6; "Written Book on Pioneer Life," Indianapolis News, December 7, 1916, 13; Obituary for Margaret Adams, Indianapolis Star, July 8, 1933, 10.

Saturday, November 3, 2018

An Irvington Childhood in the 'Forties

Editor's Note: Today's post was written by Lucia Walton Robinson, who resided at both Audubon Court and at 5840 Oak Avenue. Ms. Robinson's account spans the time period from 1937 to 1950. Her father worked as the sports director for WISH Radio and TV until 1955. He later formed the Luke Walton Advertising Agency. Ms. Robinson provides a wonderful snapshot of growing up in Irvington in the 1940s. You may read her biography at the end of the post. I have placed addresses of the families mentioned next to their names as many current residents will likely enjoy hearing stories about the people who once lived in their homes.

We’d had extended family close by in Audubon Court,

and other connections followed. On my first excursion forth a woman on a nearby

porch called to me, asked if I were my mother’s child, and brought out a

photograph of my mother at about age three with a little red chair we still

had. She was Mildred Rose, a friend of Aunt Guinevere, who lived with her

mother Mrs. Emma Kuhn (5808 Oak Avenue) a few houses away. I found other

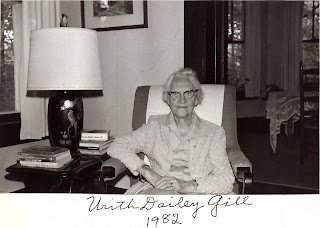

children farther up the block and later met Mrs. George Gill (5908 University

Ave.), living with her husband, sons, and Boston bulldog in an arts-and-crafts

house next to a small wood on the opposite corner of Oak and University Avenue.

Urith Dailey Gill, later an important figure in the Disciples of Christ, was a

girlhood friend of Aunt Guinevere. I often had cambric tea with her and the dog

and never told her how her younger son George, a few years older than I,

tormented me on the way to and from school 85. (George eventually became editor

and then publisher of the Louisville Courier

Journal and asked the question to which President Nixon famously answered,

“I’m not a crook.”) Every Christmas Mr. Gill would bring us a Yule log from his

wood, we “Oak Avenue Acorns” would go a-caroling, and Father would take me with

him to Clifton Wheeler’s (5317 Lowell Ave.) house to choose a lovely landscape

for Mother. A little farther up University Avenue lived the maternal grandmother

and great-aunt of my cousin Fritz

An Irvington Childhood in the 'Forties

By Lucia Walton Robinson

When I was born at the end of 1937, my parents, Luke and

Adelaide Reeves Walton, were renting a house on Johnson Avenue near the

Irvington Presbyterian Church while he worked as an announcer for radio station

WIRE and finished the last class he needed for his B.A. degree at Butler, which

he’d left in 1931. I was six months old when he left WIRE and

returned to WBOW in Terre Haute, where he’d accidentally begun his career in

broadcasting, I think in 1932, the year my sister Charlotte was born. Then in

1940 he signed on to WISH in Indianapolis and moved us to what is now known as

“Historic Audubon Court,” where Mother’s cousins Scott and June Ham were living

and I found a playmate in their youngest daughter Priscilla. Their older

daughters, Winifred and Guinevere, served often as our sitters, as did Nancy

Ostrander and Eva Ruth Ham, daughter and niece of our Great-aunt Guinevere

Ostrander (323 N. Audubon Rd.) After retiring from the State Department, The

Honorable Nancy Ostrander returned to the wonderful house on North Audubon

Road, the “mother house” of our extended family.

My memories of those first few years in Irvington are scant.

I recall playing with Priscilla and a boy my age called Jerry Pickard who lived

across the court (we made snowmen and played Superman with dishtowels attached

for capes), tagging after my sister and the older cousins, sometimes spilling

over into the alley between the court and the imposing Second Empire Layman house next door—the name Eleanor

Layman sticks in my memory, though not the person attached. Guinnie had a pet

worm that she kept in a tiny matchbox and held a funeral when it succumbed,

most likely to absence of soil. Another occasional playmate was Cousin Fritz

(Fred) Gable (5924 Lowell Ave), who lived near Aunt Guin with his parents Jane

Hall and George Gable; we were born within six weeks of each other. I think we

both attended the Hibben School, a

pleasant preschool run by two kind sisters—but I remember only a pond and

ducks. Father at that time had a sports program, possibly news, and the sort of

man-on-the-street program he’d had in Terre Haute. He was likely also doing

play-by-play of some sports events; I was too young to notice, though I’ve often

said that the first time I ever sat up was on a bleacher.

Three weeks before my fourth birthday the Japanese attacked

Pearl Harbor. It wasn’t revealed for a few months that a beloved first cousin

of my mother’s, Marine Lieutenant George Ham Cannon of Detroit, died heroically

in the concomitant bombing of Midway Island on December 7, 1941. Cousin “Hammy”

was the first Marine awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in World War

II—posthumously. His mother, Aunt Guinevere’s sister Estelle Ham Cannon,

traveled to receive it, and later to christen a small Navy ship named for him. Then,

I think all the men in the family tried to enlist, but they were mostly too old

and all except Father were 4-F. He was sworn into the United States Navy on his

six o’clock program—his first act of public relations for the Navy—and departed

for three months of officers’ training at Dartmouth College in snowy New

Hampshire, where he spent his 35th birthday. Although most

“ninety-day wonders” were posted to merchant ships (which German U-boats regularly

sank), Father was sent to Great Lakes Naval Training Station where he soon

became athletic public relations officer, working with the famed Bluejackets

sports teams. Some old friends from Butler were there, including Tony Hinkle

who coached the football team that famously beat Notre Dame, Bob Nipper (later

athletic director at Shortridge High School), and attorney Harry Ice and his

wife Betty. A young Irvingtonian sailor he’d inspired, who introduced himself

one day, was Howard Caldwell, Jr. (81

N. Hawthorne Lane), son of a friend of

Aunt Guinevere.

Mother sublet the Audubon Court apartment and we were

quartered first in the Somerset Hotel in Chicago, then at a house in Lake Bluff

where I was allowed into first grade at the wonderful village school, and then

a large old house on the base itself. Those were good years for us children.

Father was in contact with many famous athletes while being denied the sea duty

he so yearned for. Finally, he received orders to go to Pearl Harbor; Japan

surrendered almost immediately, and Mother returned with Charlotte and me to

Audubon Court, where Charli entered

high school at Howe and I third grade at school 57.

Father returned to us in November 1945 with shell necklaces,

leis, a minuscule grass skirt for me, and a coconut whose shell no implement

would crack—not a hammer, axe, nor hatchet. Finally, it was dropped from a

third-floor window, whereupon the sidewalk beneath was cracked but not, alas,

the coconut. He returned to work at WISH and in the summer bought the house at

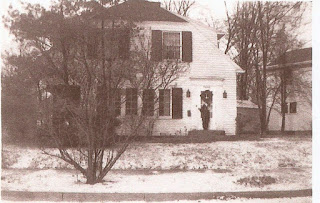

5840 Oak Avenue in south Irvington. It has been changed a great deal but was

then a charming Dutch colonial with a screened porch looking out on the side

yard with its birdbath surrounded by phlox and back-corner fish pond, which had

a lovely brick back wall with copper insert and a number of large gold and speckled

fish, one at least a foot long. A doghouse joined them when we retrieved our

Cocker spaniel Tony (named for Hinkle) from my grandmother’s, where he stayed

while we were in Audubon Court. Father was greatly annoyed every

day-after-Halloween when he had to search the neighborhood for the roof of the

doghouse. Behind 5840 was a paved area fronting a large brick wall with fireplace

where my friends and I roasted marshmallows and hotdogs on occasion and I was tasked

to burn the trash--never my favorite chore.

|

| 5840 Oak Avenue in the winter of 1946 (photo courtesy of Lucia Walton Robinson) |

Gable, now accompanied by younger brother Bruce, with an

enormous cat that was said to be 21 years old and possessed of false teeth.

When the boys visited, we played outside, as Mrs. Caroline Hall (5850

University Ave.) and “Aunt TT” (Temple Tompkins)

were rather formidable and averse to noise and activity.

|

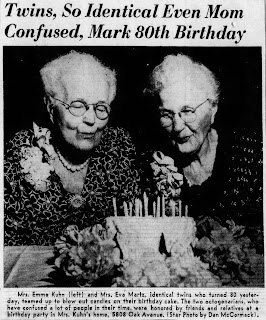

| Emma Kuhn and her daughter, Mildred Rose, lived at 5808 Oak Avenue in 1946 |

|

| Mrs. Kuhn and her sister were featured on their birthday in the Indianapolis Star in 1948. (Image courtesy of the Indianapolis Star, May 24, 1948) |

|

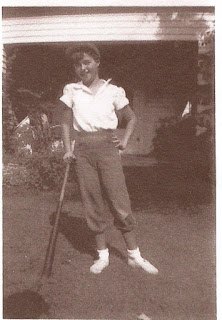

| Charlotte Walton sat upon a large boulder in front of 5840 Oak Avenue c1946. The boulder sits in the same exact spot in 2018. (image courtesy of Lucia Walton Robinson) |

Our block was populated mostly by boys; thus, sports played

a big part in my life outside school, and not only at home. Fortunately, there

was always a girl near my age in the house that had the large side yard where

we all played baseball after supper in good weather, and Jane Vogt ( 5733 Oak

Ave.) lived with her brother Charles across the street; about once a month the

three of us would board a bus for downtown to hear the children’s symphony at

Cadle Tabernacle, scowled into silence by Maestro Fabian Sevitzky. Should

anyone make a noise, the music would instantly stop and a terrifying frown search

out the culprit. Afterward, we had to cross the street to catch the bus home

and would visit the fascinating City Market, where I always bought a bunch of

sweet peas and a bag of caramels. Next to the Vogts lived the Edward Heckers

(5729 Oak Ave.). Eddie was a few years older and David I think a year younger

than I; I heard years later that Eddie was with NASA but have no corroboration.

Mr. Hecker was a printer, a kind man who wept at the funeral of their elderly

cat. He himself died suddenly shortly before we left the neighborhood, as had

the father of John Wright (5718 Oak Ave.), by several years the youngest of

four who lived on our side of the street across from the Eberts (5715 Oak Ave.).

Having four sons within a range of eight years or so, the Eberts gave over

their back yard entirely to youthful pursuits; we even rode bikes there,

pretending to be 500 drivers. I can still hear Mrs. Ebert calling “Bobby Dicky

Billy DAAAveee!” Billy was the one my age. Young Davy was allowed in our

confirmation class at Irvington Presbyterian Church because it was the last for

Dr. John Ferguson, who had confirmed his older brothers. I remember Dr.

Ferguson coming into the sanctuary when we were rehearsing, I looking up and up

and up into the benevolent face of a very large man whom Dr. Ferguson

introduced as his successor Dr. Howard Stone, telling us we would like him. It

was not so much a remark as a command, but we found the order had been

unnecessary.

|

| The Vogt Family resided at 5733 Oak Avenue. In this photo, Jane and Chuck Vogt posed next to a new bike in 1948. (image courtesy of Chuck and Joyce Vogt) |

|

| The Wright family lived at 5718 Oak Avenue. |

|

| The Ebert family lived at 5715 Oak Avenue. |

I was taken to the 500-mile race at age eight, to the first

race after the war, and would continue to attend through my college years, so I

could tell the other children whatever I could learn from a pretty low vantage

point. The race took all day in those years; Father would have to get

downtown quickly afterward to make his

six o’clock sports program, so he’d follow the police car that was transporting

the movie star brought in to kiss the winner. I can remember watching him

across the track eating box lunch with Loretta Young, her large white pumps

parked on the wall of the pit area, and wondering what my mother was thinking beside

me in the paddock. In the late ‘40s Father conceived the idea of the

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Radio Network; he shared it with Wilbur Shaw,

Wilbur talked Tony Hulman into it, and the 500 went on the air, with announcers

stationed at various points around the track and a coordinator in the Pagoda. The

broadcast went only to military bases overseas and other places at a distance

because Mr. Hulman feared local coverage would lessen attendance, as he did for

a long while with television. When I was at Duke in 1960 I drove halfway to

Raleigh to be able to hear the race.

Father’s chosen spot for the 500 was at the start and in the

front pit, and in opening the first broadcast he christened it the “greatest

spectacle in racing,” a phrase reporters are still using. After Shaw was killed

in 1954, Tony Hulman, a shy man, had to be persuaded to open the race, and he

did so on condition that Father would rehearse him and be with him at the start.

Every year they rehearsed “Gentlemen (later, “Lady and Gentlemen”), start your

engines,” and after Anton Hulman died Mrs. Hulman rehearsed with Father and

held his hand for support while she started the race. Father kept the start and

the front pit until at some point in his late 70s he almost didn’t get over the

wall in time when a car came rolling in and his colleagues insisted he give it

up.

Not long after the war Father began broadcasting the

Indianapolis Indians’ baseball games, and baseball became a big part of our

lives from spring training until late fall. Being small, I was far from a champ

in the neighborhood, usually relegated to boring left field, so Father taught

me to pitch a curve ball, which I did with sufficient skill to become a real

part of neighborhood games. Still, I spent many evenings and Sunday afternoons

in the press box at the old Victory Field, learning to score and fetching the

hot dogs that tasted better than any before or since. I remember Donie Bush and Al Lopez and a time when

Johnny Mize and Billy Martin, who’d been sent down from the Yankees to beef

up—was it Kansas City?--for a short time were in town; they had been on the

Great Lakes team (I have a baseball Mize hit a home run with there); they all

visited in Mr. Bush’s office after the games, and we drove them to Union

Station when they left. Mother and I enjoyed going to Florida for spring

training, when Father would tape interviews with the players.

|

| Luke Walton at Luke Walton Appreciation Night at Victory Field in 1952 (image courtesy of Lucia Walton Robinson) |

Irvington Presbyterian church, where Aunt Guin was a “lady

elder” and which my parents joined when Charlotte wanted to be confirmed, began

to play a significant part in our lives—mostly mine at first, as my parents

were pretty much Christmas and Easter Christians then, while I attended Sunday school,

church, vacation Bible school, and later Westminster Fellowship. At some point

Father was drafted to narrate the Christmas Eve services, which he continued to

do for decades; Mother was a star of the Irvington Dramatic Club, which met at

the church. Father’s first baseball sponsor was Sterling Beer, and Dr. Ferguson

went to see him about it. “Luke, you don’t drink alcohol, do you?” Father

didn’t. Dr. Ferguson pointed out that large numbers of boys and young men were

listening to those baseball broadcasts and asked him if beer was really what he

wanted to be pitching to them. Father hadn’t thought about that; he spoke with

the station managers, and subsequently his sponsor became Stokely-Van Camp, so

a lot of “tall cans of corn” were hit and balls batted into “Stokely’s pea

patch.”

In 1949, professional basketball came to Indianapolis in the

form of the Indianapolis Olympians, with a nucleus of former Kentucky Wildcats

whose exciting fast-break basketball lured me to sit behind Father as he

broadcast their games in the Butler Fieldhouse. Most of them had nice wives who

sat next to us, and I thought I might marry the lone bachelor when I grew up.

Father wrote a book about them, Basketball’s

Fabulous Five, but sadly some dishonest actions on the part of two of the

players while in college came to light after a few years; Father withdrew the

book, and the remarkable team was no more. I went on to Shortridge and cheered

the Blue Devils in the high school tournaments with friends, no longer sitting

with Father.

A few years ago my daughter and I visited our Irvington

cousins at Halloween, and I was delighted to see that the old celebration,

which in my childhood comprised painting pictures on storefront windows and an

evening parade, has not only continued but grown to a full-scale festival. I

remembered parading with John Wright as Tom Sawyer (me) and Aunt Polly (John,

augmented with pillows and a wig), and reflected that that was far from the

only time John wore skirts, as he was spirited away to St. Meinrad’s Seminary

after eighth grade, eventually to become a Catholic priest. Finding his

obituary online, I learned that he served as a Navy chaplain for thirty years

and retired in San Diego with “Monsignor” before his name. Years ago I heard

that three of the Ebert boys had also become ministers, another reflection of

the influence of John Ferguson and Howard Stone.

Shortly before my friend John left for seminary, our family

left Irvington for the north side, where Father was closer to his golf club and

Charlotte to Butler, and I found lifelong friends at school 70 and Shortridge

High School. I began my journey into Episcopalianism at that time though Dr.

Stone persuaded Father to teach the high school class at Irvington Presbyterian,

where he became a deacon and then an elder of the church and where all our

family weddings, baptisms, and funerals have been held as well as Luke and

Addie’s 50th wedding anniversary party. Of the extended family, Cousins

Nancy Ostrander and Bruce and Carol Gable remain in Irvington, and Cousin Fred

has returned. Much has changed in the nearly seventy years since we left Oak

Avenue, but it is good to see that many of Irvington’s unique qualities and

landmarks survive.

One change I was sad to see in Irvington was the absence of

the Hilton U. Brown house (5087 East Washington St.) on what used to be Brown’s

Hill. Among the first books I ever read was my sister’s copy of his daughter

Jean Brown Wagoner’s Louisa May Alcott:

Girl of Old Boston in Bobbs-Merrill’s Childhood of Famous Americans series,

followed by her Jane Addams. When we

returned to Irvington after the war, Mrs. Wagoner, another friend of Aunt

Guinevere, had her Martha Washington

in galleys and asked if I’d read it, see how I liked it and whether it lagged

anywhere. That was my introduction to publishing. Father wrote Basketball’s Fabulous Five about the

Indianapolis Olympians later, and I proofread that. I edited the literary

magazine and a few professors’ books in college, decided on a career in

publishing, and had my first job with Bobbs-Merrill’s incipient college division.

My inscribed copies of Mrs. Wagoner’s books are now with the Irvington

Historical Society.

Biographical note: Holding

degrees from Butler and Duke Universities, Lucia Walton Robinson has edited

books in Indianapolis and Manhattan, raised two highly literate people, and

taught literature and writing in a Gulf Coast college. Now retired near the

Carolina coast and her daughter, also an editor and poet, she has returned to

writing and editing. Her work has appeared in The Penwood Review, The Road Not Taken: A Journal of Formal Poetry,

Kakalak, Split Rock Review, Indiana Voice Journal, Spirit Fire Review, and other publications.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)